- Joined

- Apr 14, 2013

- Messages

- 9,755

- Reactions

- 5,122

- Points

- 113

Preliminary Note

This post is the first in a planned series in which I explore related topics, such as tennis generations, the current sea change that (I believe) is finally occurring, and perhaps a look at the up-and-coming generations, to try to sort out who will rise to the top. I will add new posts to this thread over the next weeks, rather than start new threads, so if interested, keep checking the thread for further installments.

With Daniil Medvedev's victory over Novak Djokovic at the US Open, it is tempting to say--finally--that the changing of the guard is here. It seems like it's been years now that we (or, admittedly, I) have been expecting this to occur, but the proverbial "Big Three"--Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal, and Novak Djokovic--kept re-asserting themselves over younger generations.

I don't need to recap in detail just how dominant those three players have been, but perhaps the best single stat is that since Roger Federer won his first Slam at Wimbledon in 2003, the three are responsible for 60 of 73 Slams. That 19-year span (2003-21) includes eight years in which those three players won all four Slams.

What is particularly striking is that the dominance came in several waves. The first was the classic "Fedal Era," when Roger and Rafa won every Slam from Roland Garros in 2005 to Wimbledon in 2009, with the lone exception being Novak's first Slam at the 2008 AO. After Juan Martin del Potro's upset of Federer at the 2009 US Open, the Fedal duo won every Slam in 2010, and then were joined by Novak in 2011, and then Andy Murray joined the mix in 2012, winning a Slam in both that year and 2013. So if 2004-10 was the Fedal Era, 2011-13 was the era of the Big Four.

But the first sign of the end of Big Three (or Four) dominance came in 2014, when they dropped not just one but two Slams to other players, upstarts Stan Wawrinka and Marin Cilic. But Novak reclaimed dominance over the tour in 2015, having his best year, even as Fedal were slam-less for the first time since 2002. In 2015-16 it looked like Rafa was finally losing the war of attrition to Father Time, and Roger seemed unable to get past Novak, so it seemed that the era was finally ending. But then 2017 happened, and we saw both Roger and Rafa reclaim a high level, splitting the four Slams, and the Big Three won 14 straight Slams from AO 2017 through the 2020 French Open.

Part of the problem was the weak "Lost Gen," those players born roughly from 1989 through 1993 or so (plus or minus a year, depending upon how you want to cut the cake). Until Dominic Thiem won the 2020 US Open, no player born after 1988 (Cilic and del Potro) had a Slam title to his name. In other words, as of pre-US Open in 2020, no player age 30 or younger had a Slam title - unprecedented in the Open Era, if not all of tennis history.

Thiem broke the ice for the younger generations, but then Novak re-asserted himself and won the first three Slams of 2021 before Medvedev upset him at the US Open.

So it would seem that--if we only look at Slams--there is no changing of the guard, just a couple younger guys sneaking in a Slam title in each of the last two years.

But let's dig deeper. While the Grand Slams are the crown jewels of the tournament, they aren't the only important titles. In total, there are 14 "big titles," which are essentially the main events of the ATP tour: four Slams, nine Masters and the singular year-end World Tour Finals, with every fourth year yielding a fifteenth, the Olympics. There are about a dozen ATP 500 tournaments in any given year, and about forty ATP 250s, plus a few non-tour tournaments. But these are basically "non-essential." Most top players play a few every year, but every top player--barring injury or some other circumstance--shows up for the big titles.

In other words, by looking at the big titles we can see that the guard is, indeed, changing.

A Detour into Generation Theory

Before getting into my chart below, let's take a brief detour into what I call "Generation Theory," which is a tool in which one can categorize tennis cohorts by five-year spans. This is, of course, subjective, and shouldn't be taken too seriously, both because every player develops differently, and also because any such demarcation is arbitrary. Meaning, there are always exceptions; for instance, while I group David Ferrer chronologically with Federer's generation, he really was more of a peer to Nadal and Djokovic.

But as a general rule, any given generation dominates the tour for about half a decade before giving way to the next, and using it as a hermeneutic tool yields some interesting data.

When I first came up with the idea some years back, I took the convenient fact that the two greatest players of the first decade of the 20th century, Federer and Nadal, were born five years apart, in 1981 and 1986. So I used those two years as the center-points for their respective generations, so that "Generation Federer" are those players born from 1979-83 (+/- two years from Roger's birth year, 1981), and "Generation Nadal" (now Djokodal or Nadalkovic) is 1984-88. After them is the previously mentioned Lost Generation, born in 1989-93, and then Next Gen (1994-98), and what I'm calling the Millenial Gen (1999-2003).

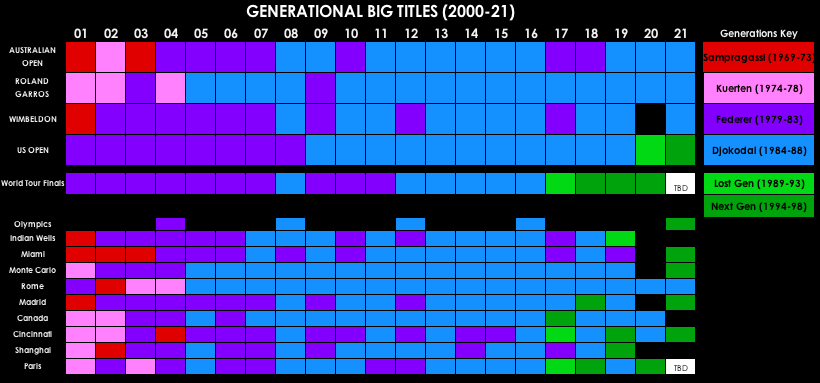

The Chart: Generational Big Titles, 2000-21

As you can see, the changing of the guard can be seen in the non-Slam big titles, with Next Genners winning six of seven of them, and six of ten big titles overall this year. In other words, the Djokodal Gen has won 40% of big titles this year compared to 62.5% in 2020. Even if they win the WTF and Paris, that still will yield them only half of all big titles this year.

As you can see from the chart, the changing of the guard really began in 2017, but only tentatively. 2016 saw the Djokodal Gen win all 15 big titles -- only the second time (after 2013) that they won every big title. But with Roger's resurgence in 2017, and strong performances by Grigor Dimitrov and Alexander Zverev's first big title, younger generations began to take away some of those big titles. And it was gradual, with 2018-19 still seeing that shift delayed, with younger generations still not breaking through at a Slam.

Thiem's win of the US Open in 2020 was a significant milestone; as previously mentioned, he became the first player born after 1988 to win a Slam. But he did so without defeating any of the Big Three. This year, Medvedev not only beat #1 Djokovic, in the process he prevented the Serbian great from capturing the first true Grand Slam since Rod Laver in 1969.

As a side note, 2020 also saw a Next Genner win more titles than anyone else: Andrey Rublev with 5, with Novak winning 4. But given that it was an abbreviated season and Rublev did not win any big titles, it must be marked with an asterisk. This year, four players are tied with a tour-leading four titles: Djokovic, Medvedev, Zverev, and Casper Ruud (who, being born in December 22, 1998, is technically a Next Genner, but on the cusp of the Millenial Gen).

Alright, I'll leave that there for now, but will follow-up with some further angles on this, to explore this changing of the guard, and related topics.

This post is the first in a planned series in which I explore related topics, such as tennis generations, the current sea change that (I believe) is finally occurring, and perhaps a look at the up-and-coming generations, to try to sort out who will rise to the top. I will add new posts to this thread over the next weeks, rather than start new threads, so if interested, keep checking the thread for further installments.

PART ONE: FINALLY...THE CHANGING OF THE GUARD

The Era of the Big Three Winds to an End...or Does It?With Daniil Medvedev's victory over Novak Djokovic at the US Open, it is tempting to say--finally--that the changing of the guard is here. It seems like it's been years now that we (or, admittedly, I) have been expecting this to occur, but the proverbial "Big Three"--Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal, and Novak Djokovic--kept re-asserting themselves over younger generations.

I don't need to recap in detail just how dominant those three players have been, but perhaps the best single stat is that since Roger Federer won his first Slam at Wimbledon in 2003, the three are responsible for 60 of 73 Slams. That 19-year span (2003-21) includes eight years in which those three players won all four Slams.

What is particularly striking is that the dominance came in several waves. The first was the classic "Fedal Era," when Roger and Rafa won every Slam from Roland Garros in 2005 to Wimbledon in 2009, with the lone exception being Novak's first Slam at the 2008 AO. After Juan Martin del Potro's upset of Federer at the 2009 US Open, the Fedal duo won every Slam in 2010, and then were joined by Novak in 2011, and then Andy Murray joined the mix in 2012, winning a Slam in both that year and 2013. So if 2004-10 was the Fedal Era, 2011-13 was the era of the Big Four.

But the first sign of the end of Big Three (or Four) dominance came in 2014, when they dropped not just one but two Slams to other players, upstarts Stan Wawrinka and Marin Cilic. But Novak reclaimed dominance over the tour in 2015, having his best year, even as Fedal were slam-less for the first time since 2002. In 2015-16 it looked like Rafa was finally losing the war of attrition to Father Time, and Roger seemed unable to get past Novak, so it seemed that the era was finally ending. But then 2017 happened, and we saw both Roger and Rafa reclaim a high level, splitting the four Slams, and the Big Three won 14 straight Slams from AO 2017 through the 2020 French Open.

Part of the problem was the weak "Lost Gen," those players born roughly from 1989 through 1993 or so (plus or minus a year, depending upon how you want to cut the cake). Until Dominic Thiem won the 2020 US Open, no player born after 1988 (Cilic and del Potro) had a Slam title to his name. In other words, as of pre-US Open in 2020, no player age 30 or younger had a Slam title - unprecedented in the Open Era, if not all of tennis history.

Thiem broke the ice for the younger generations, but then Novak re-asserted himself and won the first three Slams of 2021 before Medvedev upset him at the US Open.

So it would seem that--if we only look at Slams--there is no changing of the guard, just a couple younger guys sneaking in a Slam title in each of the last two years.

But let's dig deeper. While the Grand Slams are the crown jewels of the tournament, they aren't the only important titles. In total, there are 14 "big titles," which are essentially the main events of the ATP tour: four Slams, nine Masters and the singular year-end World Tour Finals, with every fourth year yielding a fifteenth, the Olympics. There are about a dozen ATP 500 tournaments in any given year, and about forty ATP 250s, plus a few non-tour tournaments. But these are basically "non-essential." Most top players play a few every year, but every top player--barring injury or some other circumstance--shows up for the big titles.

In other words, by looking at the big titles we can see that the guard is, indeed, changing.

A Detour into Generation Theory

Before getting into my chart below, let's take a brief detour into what I call "Generation Theory," which is a tool in which one can categorize tennis cohorts by five-year spans. This is, of course, subjective, and shouldn't be taken too seriously, both because every player develops differently, and also because any such demarcation is arbitrary. Meaning, there are always exceptions; for instance, while I group David Ferrer chronologically with Federer's generation, he really was more of a peer to Nadal and Djokovic.

But as a general rule, any given generation dominates the tour for about half a decade before giving way to the next, and using it as a hermeneutic tool yields some interesting data.

When I first came up with the idea some years back, I took the convenient fact that the two greatest players of the first decade of the 20th century, Federer and Nadal, were born five years apart, in 1981 and 1986. So I used those two years as the center-points for their respective generations, so that "Generation Federer" are those players born from 1979-83 (+/- two years from Roger's birth year, 1981), and "Generation Nadal" (now Djokodal or Nadalkovic) is 1984-88. After them is the previously mentioned Lost Generation, born in 1989-93, and then Next Gen (1994-98), and what I'm calling the Millenial Gen (1999-2003).

The Chart: Generational Big Titles, 2000-21

As you can see, the changing of the guard can be seen in the non-Slam big titles, with Next Genners winning six of seven of them, and six of ten big titles overall this year. In other words, the Djokodal Gen has won 40% of big titles this year compared to 62.5% in 2020. Even if they win the WTF and Paris, that still will yield them only half of all big titles this year.

As you can see from the chart, the changing of the guard really began in 2017, but only tentatively. 2016 saw the Djokodal Gen win all 15 big titles -- only the second time (after 2013) that they won every big title. But with Roger's resurgence in 2017, and strong performances by Grigor Dimitrov and Alexander Zverev's first big title, younger generations began to take away some of those big titles. And it was gradual, with 2018-19 still seeing that shift delayed, with younger generations still not breaking through at a Slam.

Thiem's win of the US Open in 2020 was a significant milestone; as previously mentioned, he became the first player born after 1988 to win a Slam. But he did so without defeating any of the Big Three. This year, Medvedev not only beat #1 Djokovic, in the process he prevented the Serbian great from capturing the first true Grand Slam since Rod Laver in 1969.

As a side note, 2020 also saw a Next Genner win more titles than anyone else: Andrey Rublev with 5, with Novak winning 4. But given that it was an abbreviated season and Rublev did not win any big titles, it must be marked with an asterisk. This year, four players are tied with a tour-leading four titles: Djokovic, Medvedev, Zverev, and Casper Ruud (who, being born in December 22, 1998, is technically a Next Genner, but on the cusp of the Millenial Gen).

Alright, I'll leave that there for now, but will follow-up with some further angles on this, to explore this changing of the guard, and related topics.

Last edited: